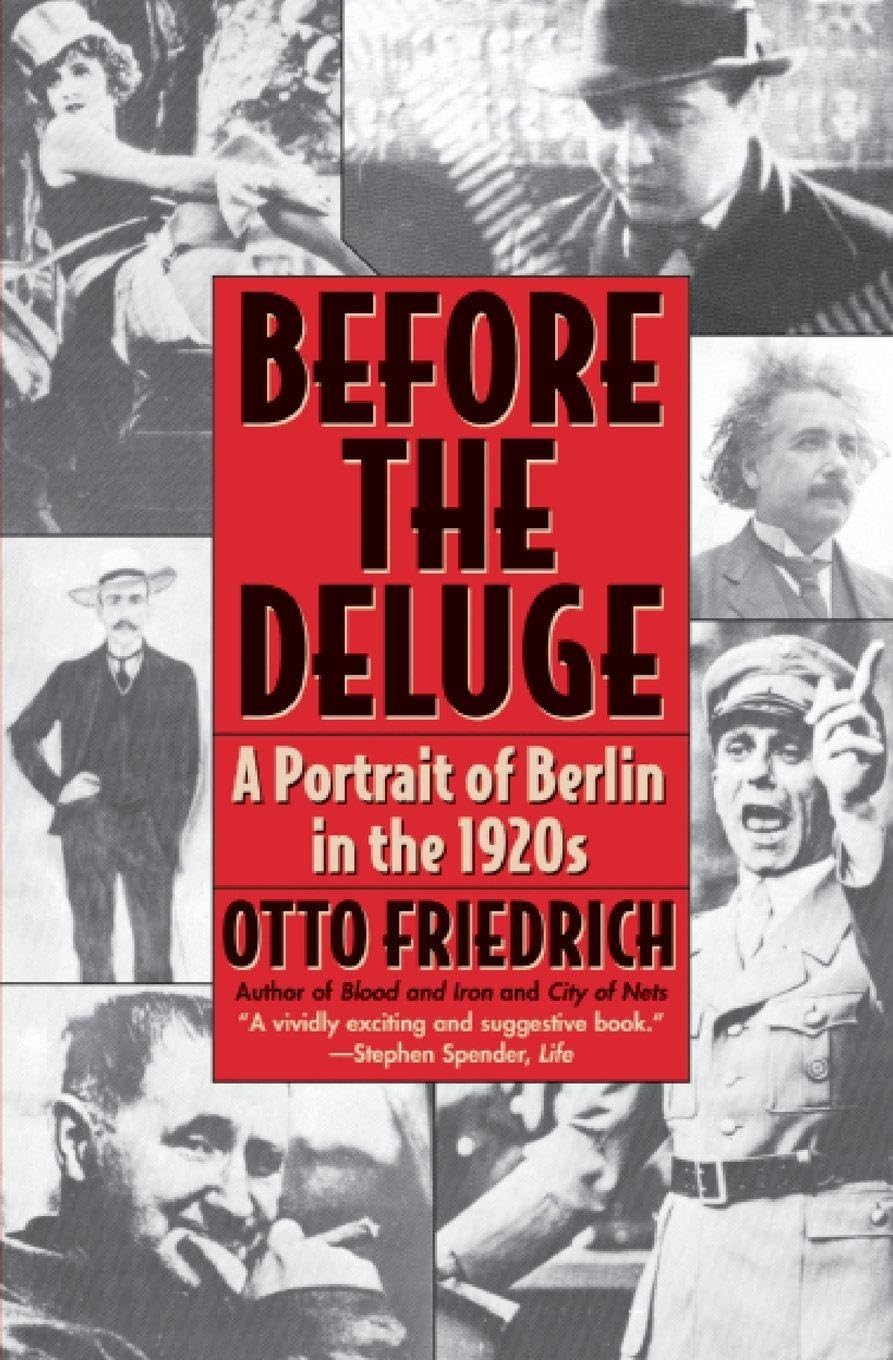

Description

A fascinating portrait of the turbulent political, social, and cultural life of the city of Berlin in the 1920s. "What a story...in a class with the best of Barbara Tuchman....He has written a splendid book."--Wolf Von Eckhardt, "Washington Post""It is Otto Friedrich's grasp of dramatic unity which makes this such a vividly exciting and suggestive book....we are able to see not only the tragic events but also the rich and varied life."--Stephen Spender, "Life"""Before the Deluge" recaptures in an eerie but only too authentic manner the tawdry, dangerous, and undeniably exciting story of the sickness which overcame Germany in the '20s....No place in the world was so creative and decadent, so despairing and exhilarating....What "Cabaret" did in musical form Friedrich has captured here."--Harrison Salisbury"A fascinating portrait of a city where art and riot flourished side by side and incredibility was the normal state of things."--"Atlantic Monthly" A fascinating portrait of the turbulent political, social, and cultural life of the city of Berlin in the 1920s. Otto Friedrich (1929-1995) was a journalist and cultural historian. A contributing editor at The Saturday Evening Post and Time magazine, he was the author of fourteen books, including Before the Deluge: A Portrait of Berlin in the 1920s . "What a story...in a class with the best of Barbara Tuchman....He has written a splendid book." The Birds of Berlin PROLOGUE Therefore let us found a city here And call it "Mahagonny," Which means "city of nets." . . . It should be like a net Stretched out for edible birds. Everywhere there is toil and trouble But here we'll have fun .... Gin and whiskey, Girls and boys . . . And the big typhoons don't come as far as here. --BERTOLT BRECHT "Would you like me to show you?" the old man asks. Professor Edwin Redslob is more than old; he is ancient, a survivor of almost a century of violence. He was already in his mid-thirties when Germany's broken armies came straggling home from the First World War, and now he is eighty-six, tall and smiling and white-haired. He can hardly see through the thick lenses that fortify his eyes, but he totters across his dusk-darkened studio, past the window that opens onto the white-blossoming apple trees in the garden, and then he bends over a wooden cabinet that contains his treasures. As an art expert, he joined the Interior Ministry more than fifty years ago to help the nascent Weimar government create a new image for the new Germany, and he began by commissioning a young Expressionist painter named Karl Schmidt-Rotluff to redesign the most fundamental image, the German eagle. Now he bends over a shallow drawer, grunts and fumbles through a sheaf of pictures, and finally pulls forth the one he wants: the Weimar eagle. He holds it high, gazing at it with affection. The eagle boasts all the pride and dignity of its imperial ancestors, black wings spread wide, beak hungrily open, but it has other qualities as well. It seems less grim than the traditional eagle; indeed, it seems almost cheerful, a friendly eagle. "A marvelous thing," says Dr. Redslob. "But the number of insults that this picture provoked--you wouldn't believe it." It is a mistake, perhaps, to attach too much importance to symbols. In the Berlin Zoo, there is a real eagle--two of them, in fact--and we can stand outside the cage and regard the imprisoned beast that we consider the German symbol, and our own. At the base of an artificial tree, there lies a pool of rather dirty water, and one of the eagles slowly lowers its claw-feet into the pool and begins picking at the bloody carcass of a rabbit that has been left there to satisfy its appetite for carrion. In the tranquillity of the Zoo, there are cages for every variety of giant bird-huge hawks wheeling restlessly within the limits of their confinement, flamingos folding and unfolding themselves, and even some mournful marabous, which stand in stoic silence and stare back at their visitors. Wandering loose in the Zoo, ignoring the elephants and the rhinoceroses, there are dozens of mallards, always two by two, the green-headed male trailed by his speckled brown and white mate. Nor do they remain in the Zoo. They float among the swans in the canals outside the Charlottenburg Palace. They roam among the chestnut trees in the Tiergarten. They nibble at weeds in the Havel River. "You don't have ducks like that in American cities?" a Berliner asks in surprise. "Here they are everywhere." Berlin, more than almost any other great city, is a city of birds. One hears not only sparrows chirping in the midst of the traffic on the Kurfurstendamm but wood thrushes singing in the Glienicker Park. One sees species one never expects to find in cities-magpies and nightingales and a black-feathered, yellow-beaked diving grebe known as a "water chicken." Even at the Hilton Hotel, the traveling businessman wakes to the sound of peacocks screeching in the night. One reason for

More Information

| Gtin | 09780060926793 |

| Mpn | Illustrations, Map |

| Age_group | ADULT |

| Condition | NEW |

| Gender | UNISEX |

| Product_category | Gl_book |

| Google_product_category | Media > Books |

| Product_type | Books > Subjects > History > Europe > Germany |